Any parent or teacher will tell you that, while sharing some similarities, each kid is different, even within the same age group or the same family. The same kid will be different at different times of the day and in different contexts, just like adults. It seems an obvious point. Yet, as adults we are often guilty of generalizing, discussing kids as a homogenous group when describing how they learn, how they engage with technologies, how to empower them, and how to protect.

May 2013

On the freeway turnoff for the university, I saw their yellow school bus, seeming large compared with the small heads in the seats. The students were an hour early. As I parked, they were already running up the stairs to the fourth floor. I got to the stairs, looked up the flights, took a deep breath and ran after them.

Already, this didn’t feel like teaching college.

Once a year, students from the Harding University Partnership School in Santa Barbara visit UC Santa Barbara and participate in a lesson/activity to introduce them to college. Six grades were on the campus that day, with others visiting the touch tanks at the Marine Science labs, or exploding things with the Teacher Education Program’s Science faculty. I’d worked a bit with elementary and high school students before finishing my degree, but in the intervening years, have felt like I’m spending more time reading and researching kids than working directly with them, so volunteered to help with the lesson.

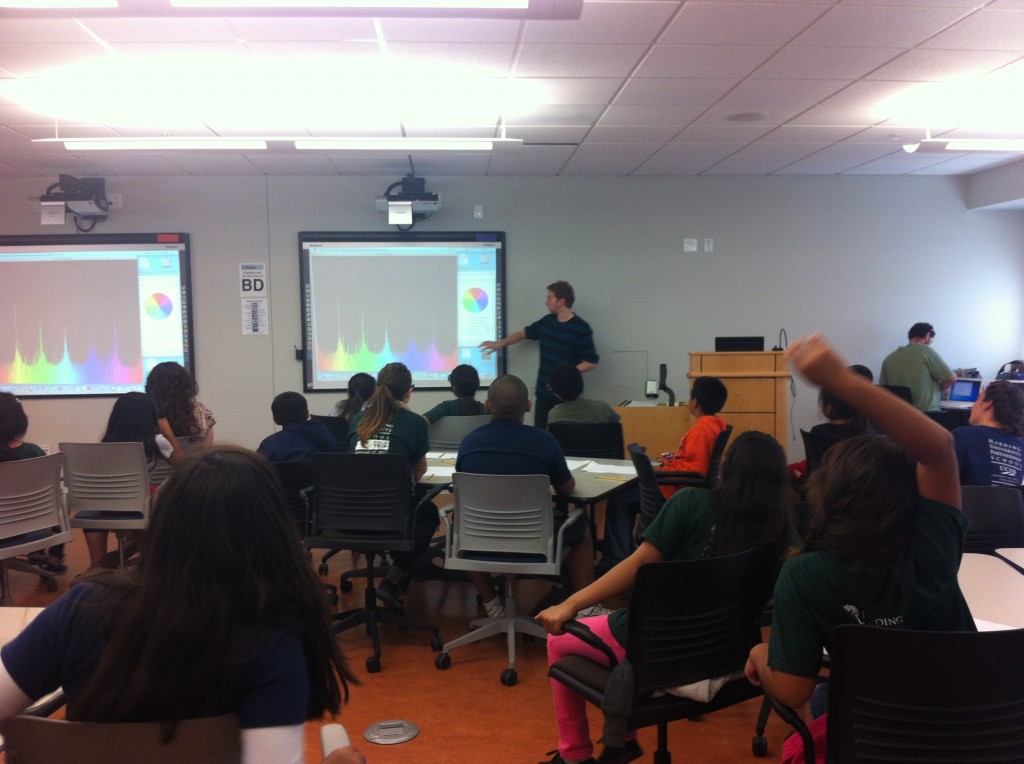

By the time I got to the classroom, the 56 students were in their seats, seated in groups of 5-7 with a teacher, teaching assistant, UCSB grad student, or parent at each table. Patrick Faverty, a lecturer in UCSB’s Teacher Education Program was already leading the class. The lesson was about framing and perspective, with a goal of showing the students that things looked different depending on the frame or perspective used to view them. Faverty used color and patterns to illustrate his point, including photos of deserts and forests and geometric shapes, all from California, to complement the work their class had done on California history and geography. He then assigned the activity: the students would spend 30 minutes exploring the campus and use cardboard frames to select objects with interesting colors or patterns and then photograph them.

Walking out of the classroom, one of the girls said to Faverty, ‘um, you’re pretty.’ Her friend giggled. Faverty, not missing a beat said, ‘pretty ugly, huh!’ The girls erupted in giggles as we started down the stairs. Some boys came up to say the same, but realized we were on to them. Downstairs, we started helping with framing, repeating instructions for the activity, asking and answering questions, and providing tech support if the students had trouble with the cameras.

Of course, the students saw more in the downstairs garden than I had noticed. One admired the varying blues and greens in a shady part of the garden. Others ran ahead to scope out spots for their photos. A few were disinterested and staring at the lawn. The class had been to Lotusland the day before, so were filled with questions. Is this a succulent? How often is it watered? Where is the shade garden? What kind of aloe is this? Our small group of 7 girls wandered around, helping each other take pictures, each holding the frame for a moment and passing it on as they took their picture. There were the kids who immediately knew what they wanted to photograph, others who asked for suggestions of what to photograph, others who took their pictures quickly, and one who seemed very embarrassed when it was her turn.

We finished early and all at once the girls asked if they could roll down the lawn. I had never considered it a hill, but looking at it in the sunshine, it definitely beckoned. I looked at the teacher aides and they shrugged and that’s all the students needed to run up the short hill and start rolling down. Then they got the idea that this moment is what they should photograph and they had one picture left. The girl who had been embarrassed earlier enthusiastically grabbed the camera and photographed them rolling down.

We finished early and all at once the girls asked if they could roll down the lawn. I had never considered it a hill, but looking at it in the sunshine, it definitely beckoned. I looked at the teacher aides and they shrugged and that’s all the students needed to run up the short hill and start rolling down. Then they got the idea that this moment is what they should photograph and they had one picture left. The girl who had been embarrassed earlier enthusiastically grabbed the camera and photographed them rolling down.

Of course, they had wet grass all over their clothes and formed a line to dust each other off. And, of course, a couple students ended up being mildly allergic to grass.

Of course, they had wet grass all over their clothes and formed a line to dust each other off. And, of course, a couple students ended up being mildly allergic to grass.

Back in the classroom, the students seemed most interested in the swiveling office chairs. There was much experimenting with height and whether it affected velocity as they spun around. We were waiting for all of the groups to return. The chair chitchat prompted one of the students to ask me what college is like. “Well,” I said, “you can come to school whenever you want, you can arrange your schedule for two or three days a week if you want.” I paused, thinking of something more inspiring to say, and she said to her friends, “Did you hear that? College is cool, you don’t have to go to school every day!” As if to punctuate, she used pushed a button on the chair and sunk to the ground.

Another student asked more about the aloe we’d seen with thorns on it. I had never seen one before either, so I looked it up on my iPhone. A few students leaned in, offering suggestions for search terms and I asked which link we should follow. “Wiki” one of them offered and the others nodded. So, we looked at wiki answers and the website addressed the usual spines of an aloe, not quite thorns. We discussed and were in the midst of a second search when I had to quickly move to the other side of the table because there had been some sort of commotion involving chair adjustments.

I was back in what seemed like less than 3 minutes, but the girls were already looking at pictures on my phone. Throughout the morning activity, there had been several people taking photos, news reporters, the department PR, and the volunteers. The kids didn’t seem to care,but now, one looked up and asked, “why are there pictures of us?” I said I was glad she asked, and explained that I basically take pictures of everything, and here I took pictures to record the activity and since the cameras the kids were using kept erasing their pictures, I took duplicates of their pictures, too, as best I could. She shrugged and said ok, and kept thumbing through, sharing pictures with the other girls.

I led the larger group in a writing activity listing what they liked and what they saw in preparation to write a poem about their experience. Walking around the room, I reflected on the morning. A first rule of teaching is to be flexible and prepared for the unexpected, because it always happens. The students arriving early, playing with the chairs, and rolling down the lawn were just a few of the day’s surprises.

Second, any parent or teacher will tell you that, while sharing some similarities, each kid is different, even within the same age group or the same family. The same kid will be different at different times of the day and in different contexts, just like adults. It seems an obvious point. Yet, as adults we are often guilty of generalizing, discussing kids as a homogenous group when describing how they learn, how they engage with technologies, how to empower them, and how to protect.

Depending on the frame, it’s easy to pick out kids who are enthusiastic users of technology, for example, who enjoy taking photos and seeing their photos used in the classroom. Yet it would be just as easy to pick out kids who weren’t interested in taking pictures or didn’t seem to care what was discussed in the larger group later, even when their photo was discussed. Then there were kids in the middle, interested at points and then distracted by something else. So, depending on the frame, I could use the conversations with my small group about the photos to say that kids are critically aware of how their images are used, or concerned about their privacy, or just interested in pictures of themselves. If I probed further, I may find that kids disinterested in the activity might be interested in similar activities outside of class, or maybe not.

I could use similar framing to describe how some of the students immediately started to look at photos on my iPhone, or recommended search terms. While each of these framings may be true in part, they risk missing the larger story, that each classroom is filled with students operating at different levels of interest, attention, capability. Zooming in is important to get a sense of individual needs but this must be balanced with a wider view of the diversity of needs and capabilities demonstrated by the students. Often, stories of technology and learning focus on ‘harmonious portrayals” of technology (Selwyn, 2012), the smooth running, ideal outcomes, kids’ enthusiastic engagement. Even in ideal circumstances, this view only tells part of the story. As this sample experience shows, any given moment in the classroom includes a range of activities and interest levels, distractions and meaningful teaching moments. Behind-the-scenes on this particular day were the tech staff who had spent part of the week testing the computers, cameras, internet access, making sure all of the instructors’ phones could throw images up on the screen, testing our plans to put together booklets from the photos taken by the kids, making sure the sound worked, etc. The teachers had invited parents to help with the field trip, so we had lots of support in managing the classroom. The teachers had worked with us to create a lesson that fit with their current units.

Whether studying children, learning, educational technologies, context is critical. We are never simply looking at whether an iPad, for example helps with a science lesson, we must consider the role of the teacher, the quality of the lesson, prior knowledge, the classroom context and the social context. Instead of focusing on just the kids who engage, the kids who are disinterested or mildly interested are an interesting part of the story — perhaps not the harmonious or even magical view of tech that other stories tell, but a more complete and honest account that can help us better understand the interactions moving forward.

Whether studying children, learning, educational technologies, context is critical. We are never simply looking at whether an iPad, for example helps with a science lesson, we must consider the role of the teacher, the quality of the lesson, prior knowledge, the classroom context and the social context. Instead of focusing on just the kids who engage, the kids who are disinterested or mildly interested are an interesting part of the story — perhaps not the harmonious or even magical view of tech that other stories tell, but a more complete and honest account that can help us better understand the interactions moving forward.