Imagine if, when Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone, he said, this phone is going to have applications that allow you to check e-mail, find nearby restaurants, update your Facebook, tweet, and use maps, but it’s going to be rubbish as a phone. It’s awkward to hold to your ear, it often drops calls, and most of the time, won’t get reception wherever you are. Would you have bought it? Remember, at that time, apps weren’t well known. Of course, those of you who have an iPhone can’t live without the apps now and don’t mind if it doesn’t really work well as a phone. You’re texting instead of calling anyway.

Now, we have a new mobile device, the iPad, which many describe as a reader. Sure, it has reading capacity, but the iPad isn’t a Kindle. The iPad has pinball. In fact, while it does offer business and communication apps, the iPad environment seems fraught with distraction.

What does pinball have to do with reading anyway? In my presentation last week at the Oxford Tablet Summit, I spoke about our cognitive approaches to reading. Understanding how we think is important when predicting interactions with technologies, because how our minds work doesn’t suddenly change when Apple introduces a new product.

From a cognitive perspective, the way we read remains relatively consistent, regardless of medium. As we read, our minds attempt to make sense of the content under study, comparing new information with prior knowledge, drawing connections, and forming an understanding. In an online environment, we encounter multiple media, which, depending upon their contextual relevance, may or may not support our sense-making process (see Richard Mayer’s Multimedia Learning for a thorough treatment of the topic). Regardless of medium, when content detracts from our sense-making process, our minds are prone to cognitive overload and distraction.

How much information can we handle? Cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1994) describes our minds like a glass of water. Once the glass is full, most of what is additionally poured into it will slosh over the sides. Have you ever tried to memorize a grocery list or driving directions only to realize you forgot a few of the items/steps? In 1956, Miller determined, using lists of numbers and words, that the human mind generally remembers only 7 items at a time. Test yourself. Here’s a list of words. Look at them quickly and then cover them with your hand, or scroll until they disappear.

table

electricity

aardvark

pencil

book

Oxford

stone

mirror

Now, cover up the words, or scroll up. How many words were in the list? Which ones do you remember? During the presentation, a majority of attendees remembered aardvark and Oxford, likely because they’re unusual terms. As listed though, the words do not have any significance, so they are difficult to remember. If you chunk the words–organize them into categories–they become easier to remember, allowing you to remember more than 7 words at a time. For example, table, pencil, book, and Oxford relate to each other and can therefore be chunked under a “study” category.

Stories help us make sense of information and thereby reduce our cognitive load. In the previous example, “study” gave part of the list cohesion and begins to tell a story. What word could create a story to help organize and give meaning to the following list?

table

sit

legs

seat

soft

arm

rest

This list is drawn from a study by Roediger & McDermott (1995), in which respondents generally assumed the word chair was part of the list. Since collectively the words relate to chair, this finding is not surprising. Chair is how participants made sense of the list. Thus, chair help the list tell a story.

Generally, on the Internet, stories are hard to find. We have a lot of information, but making meaningful connections is challenging. Story is a strength of newspapers. That classic who, what, when, where, why, how model that usually begins a newspaper piece is an excellent cognitive aid — it provides the information necessary for us to situate and make sense of the information. Perhaps that’s why readership remains strong even with competing content available. Our minds like stories.

So, what does story have to do with the iPad? News can contribute compelling content to the iPad reading experience. By content, I do not mean endlessly repeated AP feeds, but genuinely interesting content that provides a story to help us organize and understand key issues and daily happenings.

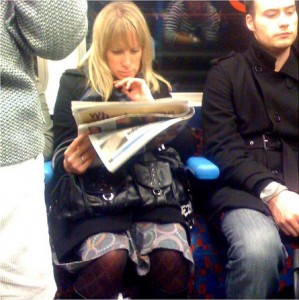

While the iPad and other technologies will certainly offer new options for delivering content, news writers should consider the ways in which their current content effectively conveys meaning. I mentioned story earlier. Using print newspapers as an example, next I’d like to explore the concept of cognitive containers.  When we open a newspaper to read it and we’re holding it in front of our faces, or glancing down at it over breakfast, we’ve essentially shut out most other inputs. It’s basically us and the page. Our attentional focus is contained: it is directed toward the text in front of us, with minimal distraction. Of course, pictures and advertisements are on the page, along with headlines for other articles, all of which can potentially distract our focus, but for the most part, we are able to immerse ourselves in whatever we’re reading.

When we open a newspaper to read it and we’re holding it in front of our faces, or glancing down at it over breakfast, we’ve essentially shut out most other inputs. It’s basically us and the page. Our attentional focus is contained: it is directed toward the text in front of us, with minimal distraction. Of course, pictures and advertisements are on the page, along with headlines for other articles, all of which can potentially distract our focus, but for the most part, we are able to immerse ourselves in whatever we’re reading.

In contrast, when we read the same article online, we encounter links within the text. Usually, clicking on these links takes us away from the page we’re reading and introduces us to new content. Moving us from our initial page is a threat to our attentional focus because we often have difficulty remembering where we started, especially if we engage in a bit of link chasing (e.g., moving to Wikipedia, following links to other websites). Added to the online reading environment is the chance that while we’re reading, we may receive an e-mail alert, IM, calendar reminder, or Twitter post that will tempt us to momentarily leave the page. In this scenario, our attentional focus is not contained. How can we develop cognitive containers like books or newspapers on iPads and other tablet devices?

When reading on a laptop or desktop screen, windows may have loosely reminded us of where we’ve been or where we’re going. We can see which applications are open and, possibly, we may see multiple browser windows or tabs. With iPad, only one window appears on the screen at a given time, so the reader has no idea how many applications are running in the background. Are iPads more distracting than laptops? Probably not. Are they more distracting than books? Absolutely. Many universities are considering delivering textbooks via some sort of e-reader. In the case of iPad, students will potentially have a wealth of distracting options to tempt them away from their reading.

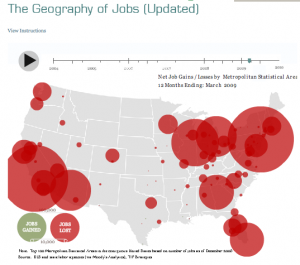

On the flip side, with careful design, content delivered on the iPad could create a cognitive container which keeps readers on the page and within the app, rather than linking to outside materials and potentially forgetting where they started. Kindle seems to succeed on this front by performing solely as a reader. At the Tablet Summit, NewspaperDirect.com demonstrated their online newspaper delivery service. The papers appeared as vivid pdfs — digital copies of the print papers, sans links within the articles. Combined with meaningful interactive graphs, such as this chart, titled “The Geography of Jobs” from Tip Strategies, Inc., newspapers could leverage the affordances of digital media while minimizing distraction.

References

Mayer, R. (2009). Multimedia Learning, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University

Press.

Miller, G.A. (1955). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on

our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 101, 343-352.

Roediger, H.L. & McDermott, K.B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering

words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

Memory, and Cognition, 21, 803-814.

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional

design. Learning and Instruction, 4, 295-312.

> Added to the online reading environment

> is the chance that while we’re reading, we may

> receive an e-mail alert, IM, calendar reminder,

> or Twitter post that will tempt us to

> momentarily leave the page.

Monica oh Monica. Its obvious you haven’t checked out all the features of the iPad. If you don’t want distractions (interrupts such as from but not limited to Twitter, Calendar events, etc.) while reading on your iPad, all you have to do is turn notifications to the off state. Sometimes I just don’t understand why do many Ph.D’s who taut their academic “intelligence” make things more complicated than they need to be? Sigh.

I love that geography of jobs map. To be perfectly fair, I am a sucker for effective interactive maps. I also really enjoy how maps can be used to convey information how you want them to. How would your reaction change for instance if the scale of the ellipses were smaller?

Eddie — thank you for your comment. The question isn’t whether the functionality exists to block potential distractions, but whether the users will actually take advantage of it. Using laptops as an example, at any time we can opt to disable our wireless access to reduce the temptation of the Internet, but do we? If we did what was good for us, companies like Pepsico and McDonald’s would be out of business.

A quote that’s been circulating blog discussions in the past month from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death seems applicable here. In it, Postman reiterates Huxley’s concern that it’s not the things we fear that will be our demise, but the things we love. My concern is that including the things we love — internet, games, means to socialize — may prove too seductive to resist and therefore are not creating an optimal environment for the type of sustained focused necessary for reading.

Aaron — good point! I’m a sucker for effective interactive maps, too. 🙂